This article was written by Stefanie Culp, SPT – a doctoral physical therapy student from the Texas State University Physical Therapy Program. She recently completed a clinical rotation at Symmetry and plans to go on after graduation to begin her career as an orthopedic physical therapist in Anchorage, Alaska.

The last two years have been a whirlwind, and not in the fun, playful way we all would have hoped for. And if you are like me, you may not have kept up with staying active throughout quarantines and altered work circumstances and the overall chaos that is the COVID-19 pandemic. But maybe, with life getting back to a “new normal”, you are thinking about getting back into the gym or starting up your previously typical exercise routine.

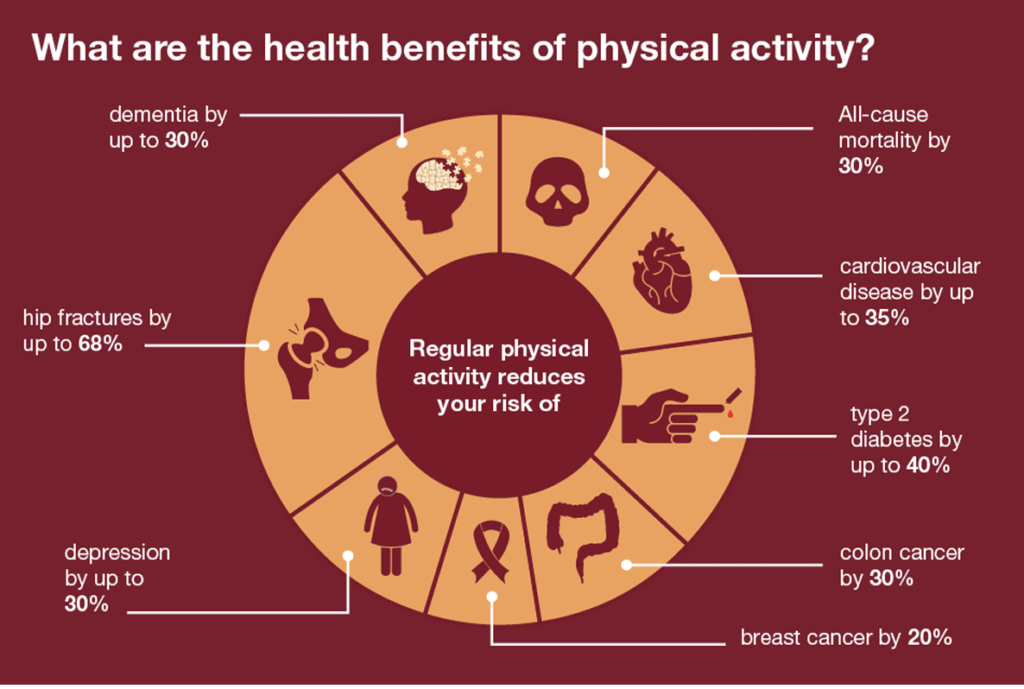

As you likely know, regular physical activity has many benefits, including improving cardiovascular and immune system health, combating obesity, preventing type II diabetes, and reducing stress, anxiety, and depression.1 Unfortunately, in the United States, only 26% of men and 19% of women report meeting recommended activity guidelines.2 How did the COVID-19 pandemic affect those stats?

Over the last two years, the daily amount of physical activity across the population has declined – due to multiple factors associated with the COVID-19 pandemic, including quarantines, gym closures, and lack of clear information on what was safe/accessible. One study of over 3,000 US adults found a 32% decrease in physical activity since March 2020. That number rose to 43% in those that had to self-isolate, which was also associated with changes in mental health.2,4 Researchers have also found an association between physical activity level and severity of COVID-19 symptoms. Physical inactivity throughout the pandemic increased the likelihood for hospitalization, admission to the intensive care unit, and death when compared to a group that consistently met recommended physical activity guidelines. This finding indicates that inactivity plays a crucial role as a risk factor for severe COVID-19 outcomes.5 interestingly, this study also found that a group of the population that partially met physical activity guidelines also had reduced risk for hospitalization and death.5 This finding supports the idea that ANY amount of physical activity can provide a protective response against illness.

So, what happens when we stop exercising?

Unfortunately, physiological changes occur rapidly (within 1-2 weeks) with significant declines in activity level.1,6 For example, within 14 days of step reduction in young and older adults, significant muscle atrophy, meaning muscle loss, can occur.1 Within that same time frame, metabolic and cardiovascular changes can occur, such as impaired aerobic capacity (amount of oxygen the body can utilize) and increased blood pressure.1,6 When these changes occur, our bodies have a lower capacity to tolerate the stresses that we put on it and tissue overload and injury could more easily occur.

Tanning and sunburns are a great analogy to use to understand tissue overload. If you gradually increase sun exposure, you will likely get a tan. But if you have been inside for the past six months with minimal sun exposure, and then spend several days outside at the Austin City Limits Music Festival over the weekend, you will likely exceed your typical sun exposure and get significant sunburn. Throughout the pandemic, your bones, tendons, muscles, cardiovascular system, etc. have acclimatized to your current level of activity or “sun exposure”. When these structures are stressed more than they are currently used to, they can either adapt or breakdown. Which response occurs depends on the load that you apply. If you haven’t walked more than 1/4 mile each day over the last six months, and you then decide to go back to walking three miles each day like you did before the pandemic, there is a possibility that you may overload your tissues or get a “sunburn”. Without proper gradual progression of activity and adequate rest and recovery as you make adaptations to your exercise routine, you may start to notice aches and pains, and possibly develop full blown overuse injuries, because those tissues have lost some of their capacity for load. The good news is that you can build that exercise capacity back up; it just takes some time and patience!

How do we safely return to activity following an extended sabbatical?

When starting a new exercise program or returning to previous activity, it is important to start slowly and progress gradually over time. If you used to walk three miles, perhaps start again with one. If you used to lift 20 pounds, perhaps start again with 10 pounds. Stick with that starting “exercise load” for 2-3 weeks to allow your body time to acclimate, and then start slowly increasing the duration of activity or the amount of weight lifted. Then repeat that adaptation process. This method of gradual training progression will ensure that you are not over-stressing your system by giving your body time to adapt to the “new” stimulus.

When deciding how to restart activity, keep in mind these FITT Principles.

- F=Frequency

- This is the number of days per week that you would perform an activity. – Start with 2-3 days of aerobic exercise/week and progress up to 5x/week.

- I=Intensity

- This is how hard you are working during exercise. – Start with low intensity and gradually increase over time.

- Utilize the “talk test” to estimate intensity. (If you are able to comfortably talk during activity, you are likely working at a fairly low intensity. More difficulty speaking while performing an activity equates to higher intensity activity.)

- T=Time

- This is the length of an activity session. – Your goal is to reach at least 30 minutes per day of at least moderate-intensity aerobic activity. Start with shorter periods of activity time and gradually increase the duration after 2-3 weeks.

- T=Type of exercise

- Pick something that you enjoy! “Exercise” doesn’t always have to be walking or lifting weights. Your mode of exercise could be anything from cycling or swimming to gardening or dancing or even regularly mowing your lawn. It’s actually a good idea to vary the activity that you perform, so that you keep different muscle groups and movement systems in optimal condition. So doing something different each day is OK.

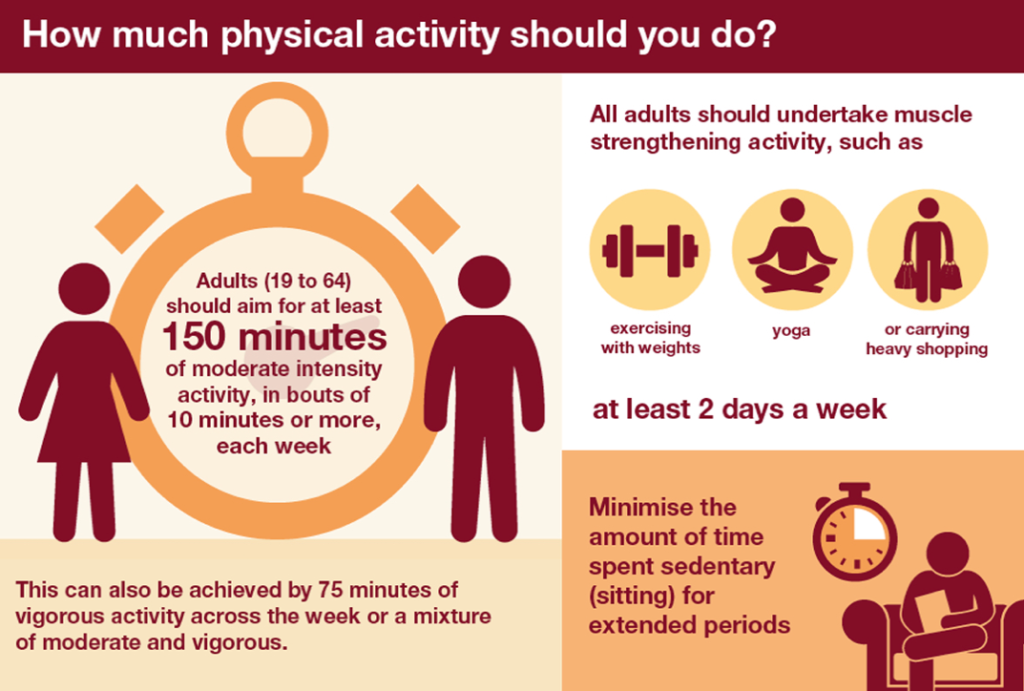

What does the World Health Organization recommend for staying healthy?

Tips for meeting these recommendations:

- If you are not already regularly active, start slowly and with low intensity activities, like walking and low impact exercises.

- Perform exercise activities about 2-3 days/week initially and gradually work up to 5 days/week or more.

- Start with shorter periods of activity, perhaps 5-10 minutes at a time if you have been sedentary previously. Gradually build up to 30 continuous minutes of activity or more over the course of a few weeks.

- Adaptation to exercise depends on the type of exercise that you are doing. (Aerobic activity and strengthening activity are somewhat different.)

- When working on increasing aerobic capacity with activities like walking, biking, or hiking, you should start to notice some positive changes after about 2-3 weeks.

- Strength gains typically start to be observed by about 4-6 weeks after initiating activity.

- Here are some examples of a few exercises that do not require large spaces or equipment:

- Aerobic exercises:

- Walking

- Stair climbing

- Yoga, Pilates, or Tai Chi

- Zumba or Dancing

- Resistance/Strength training exercises:

- Lifting/Carrying groceries

- Chair squats

- Lunges

- Pushups/Wall Pushups

- Sit-ups

- Aerobic exercises:

- Don’t wait for an injury or onset of pain before consulting a Physical Therapist about how to safely return to exercise!

- Your physical therapist is a great resource to help you to prevent injuries and to provide education and resources on exercise prescription and the safe resumption of physical activity.

References:

- Woods JA, Hutchinson NT, Powers SK, et al. The COVID-19 pandemic and physical activity. Sports Medicine and Health Science. 2020;2(2):55-64.

- Meyer J, McDowell C, Lansing J, et al. Changes in Physical Activity and Sedentary Behavior in Response to COVID-19 and Their Associations with Mental Health in 3052 US Adults. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(18).

- Health matters: getting every adult active every day. Public Health England. Published July 19, 2016. Accessed October 13, 2021. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/health-matters-getting-every-adult-active-every-day/health-matters-getting-every-adult-active-every-day

- Puccinelli PJ, da Costa TS, Seffrin A, et al. Reduced level of physical activity during COVID-19 pandemic is associated with depression and anxiety levels: an internet-based survey. BMC Public Health. 2021;21(1):425.

- Sallis R, Young DR, Tartof SY, et al. Physical inactivity is associated with a higher risk for severe COVID-19 outcomes: a study in 48 440 adult patients. British Journal of Sports Medicine. 2021;55(19):1099-1105.

- Peçanha T, Goessler KF, Roschel H, Gualano B. Social isolation during the COVID-19 pandemic can increase physical inactivity and the global burden of cardiovascular disease. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2020;318(6):H1441-h1446.